Image credit above to Avard Wooldaver https://avardwoolaver.com/avardwoolaver.com

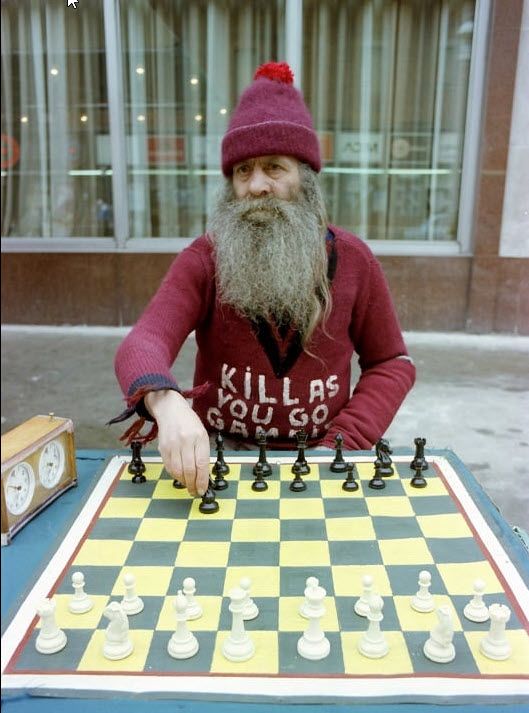

Josef (Joe) Smolij (pronounced Smoley) was not your usual chess player who wanted glory and fame in the annals of world chess domination. Joe was dedicated to chess for different reasons. He was a Polish immigrant, single, never married and without children…he was the best chess hustler on the streets of Toronto in the 70s and 80s. Those were the days when USA-Russia matches were in the headlines. He played speed chess to earn a meager income to survive. The games provided his only source of income, which hardly bothered Joe, whose motto was “I am poor in the pocket but rich in the mind.” His main social interaction with society occurred nightly until the early morning hours on the corner of Yonge Street and Gould across from Sam the Record Man store, a large music retailer at the time. He was heard to say in his heavy Polish accent “"If I vouldn't play chess, I vouldn't meet you. I am single, I am alone. I play not to be lonely, not to be drunk. Ve play for friendship. Chess on the street, chess for the people. How you like that?" The nightly ritual did much for his self esteem.

Smolij was born in Poland 1n 1921. He left home at the age of 14 to wander around Europe and spent time in Germany, Yugoslavia, Spain, France and England. Along the way he became fluent in German, Russian, English, Spanish, as well as his native Polish. He started playing chess at age 23 and honed his chess play which he called “smash-and-grab” with an aggressive style that unnerved some opponents. “Kill as you go…show no mercy.”

At 33. Smolij immigrated to Canada and eventually found a job as a machinist in Toronto. Over the last dozen years, the game of strategy became his obsession. While working, he set up a chess board next to his machine but his boss nixed that idea which left Joe back on the street almost penniless. He decided to retire early and tried to make ends meet playing chess on the street. At first he set up his board in Toronto downtown’s Allan Gardens and offered to take on any player for fifty cents (later increased to one dollar). Eventually, as sizeable crowds kibitzed over the picnic table where boisterous Joe carried out his new trade. Eventually, the police kicked him out of the park thinking it was a front for dealing drugs.

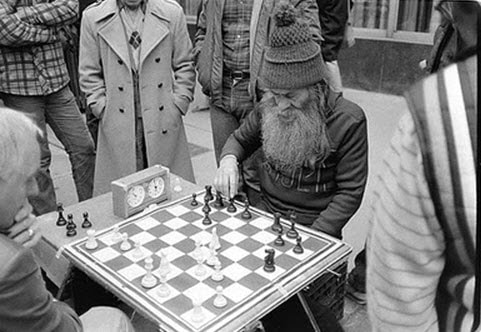

Never to be discouraged, he moved his chess business to the busy intersection of Yonge and Gould. Yonge was known as the Broadway of Toronto, marked by theaters, dance halls, flashing lights, and pin-ball arcades. Over the next two decades, this corner became the chess Mecca of Toronto. A canopy and chess tables were eventually added to the sidewalk along Gould by the city. King Smolij reigned in this corner of his chess world from 8:00 PM to 6:00 AM nightly for a decade without fail, no matter what inclement weather nature was dishing out (Toronto winters are harsh).

Josef (Joe) Smolij (pronounced Smoley) was not your usual chess player who wanted glory and fame in the annals of world chess domination. Joe was dedicated to chess for different reasons. He was a Polish immigrant, single, never married and without children…he was the best chess hustler on the streets of Toronto in the 70s and 80s. Those were the days when USA-Russia matches were in the headlines. He played speed chess to earn a meager income to survive. The games provided his only source of income, which hardly bothered Joe, whose motto was “I am poor in the pocket but rich in the mind.” His main social interaction with society occurred nightly until the early morning hours on the corner of Yonge Street and Gould across from Sam the Record Man store, a large music retailer at the time. He was heard to say in his heavy Polish accent “"If I vouldn't play chess, I vouldn't meet you. I am single, I am alone. I play not to be lonely, not to be drunk. Ve play for friendship. Chess on the street, chess for the people. How you like that?" The nightly ritual did much for his self esteem.

Smolij was born in Poland 1n 1921. He left home at the age of 14 to wander around Europe and spent time in Germany, Yugoslavia, Spain, France and England. Along the way he became fluent in German, Russian, English, Spanish, as well as his native Polish. He started playing chess at age 23 and honed his chess play which he called “smash-and-grab” with an aggressive style that unnerved some opponents. “Kill as you go…show no mercy.”

At 33. Smolij immigrated to Canada and eventually found a job as a machinist in Toronto. Over the last dozen years, the game of strategy became his obsession. While working, he set up a chess board next to his machine but his boss nixed that idea which left Joe back on the street almost penniless. He decided to retire early and tried to make ends meet playing chess on the street. At first he set up his board in Toronto downtown’s Allan Gardens and offered to take on any player for fifty cents (later increased to one dollar). Eventually, as sizeable crowds kibitzed over the picnic table where boisterous Joe carried out his new trade. Eventually, the police kicked him out of the park thinking it was a front for dealing drugs.

Never to be discouraged, he moved his chess business to the busy intersection of Yonge and Gould. Yonge was known as the Broadway of Toronto, marked by theaters, dance halls, flashing lights, and pin-ball arcades. Over the next two decades, this corner became the chess Mecca of Toronto. A canopy and chess tables were eventually added to the sidewalk along Gould by the city. King Smolij reigned in this corner of his chess world from 8:00 PM to 6:00 AM nightly for a decade without fail, no matter what inclement weather nature was dishing out (Toronto winters are harsh).

On any given night, Smolij departed his boarding house and pushed a shopping cart filled with chess paraphernalia to his chess corner where chess aficionados, fans and chess newcomers gathered to play the world’s oldest game and watch the king hold sway over his court. He would take on challengers for $1.00 per game of speed chess. It is said that he only lost about one game every two weeks. When he did lose, it was not done graciously … often being thrown out of tournaments for yelling at opponents. With a hysterical voice, he would demand another game. For Joe, losing was to experience a moment’s death. While most of the other players were quiet and thoughtful, Smolij played impulsively, grabbing pieces and slapping his time clock almost simultaneously … often pontificating on the mistakes of his opponents. “In Russia,” he would boldly state, “they send you to Siberia for that one. Yes, is true. Player scared to make bad moof [sic] in Russia.”

Smolij gave this advice to a cocky 18 year-old who challenged him: “You play good game but you lose. Must watch whole board. Sixty-four squares. You lose but you learn. You young. Lots of time. For me, no much time. I must always play hard. Can’t afford to lose. You want to become master? Only one way. You must sell car, sell home, sell wife, sell everything, read chess book, practice ten hours a day. If you lose — sleep under bridge!”

As Smolij moved from opening gambit, smash-and-crash, to eventual checkmate, his games came with a barrage of Polish-accented bravado. His jabbering during play often infuriated his opponents and entertained those who were there to watch. His skill at speed chess, his quirky demeanor, and eccentric boisterous style of play earned him infamy as an iconic fixture in Toronto. He landed a spot in the Guinness Book of World Records for a while as the world’s fastest chess player, often destroying hopefuls in short order.

In 1985, Smolij was admitted to Wellesley Hospital suffering from severe gall stones and hypothermia. Some brain damage resulted but it did not affect chess playing ability. After spending several years in a Toronto nursing home, Joe was reunited with a sister he had not seen since World War II. Smolij said it was a “miracle of miracles.” He eventually moved to Berlin, Germany to live with her.

In 2016, Josef Smolij was in a showcase of 220 portraits at the Toronto Public Library. This exhibition highlighted everyday people who lived and worked in the city throughout the 20th century. The visages, drawn largely from the Toronto Star newspaper archives, told a unique tale of each person. Smolij became a celebrity in his day simply by enduring, i.e., sleeping only four hours and playing chess all night outside in all seasons.

Chess matches continued on at Yonge and Gould, which was named Hacksel Place in honor of another chess enthusiast, until 2003. Today, the street corner across from the Sam the Record Man store, which was the Mecca of chess in Toronto has withered away over time. The city allowed maintenance to slide and some of the seats at the chess tables are missing and the wood trim around their tops is rotting. While chess is still active in Toronto, it is not as colorful as the 1970s.

Smolij gave this advice to a cocky 18 year-old who challenged him: “You play good game but you lose. Must watch whole board. Sixty-four squares. You lose but you learn. You young. Lots of time. For me, no much time. I must always play hard. Can’t afford to lose. You want to become master? Only one way. You must sell car, sell home, sell wife, sell everything, read chess book, practice ten hours a day. If you lose — sleep under bridge!”

As Smolij moved from opening gambit, smash-and-crash, to eventual checkmate, his games came with a barrage of Polish-accented bravado. His jabbering during play often infuriated his opponents and entertained those who were there to watch. His skill at speed chess, his quirky demeanor, and eccentric boisterous style of play earned him infamy as an iconic fixture in Toronto. He landed a spot in the Guinness Book of World Records for a while as the world’s fastest chess player, often destroying hopefuls in short order.

In 1985, Smolij was admitted to Wellesley Hospital suffering from severe gall stones and hypothermia. Some brain damage resulted but it did not affect chess playing ability. After spending several years in a Toronto nursing home, Joe was reunited with a sister he had not seen since World War II. Smolij said it was a “miracle of miracles.” He eventually moved to Berlin, Germany to live with her.

In 2016, Josef Smolij was in a showcase of 220 portraits at the Toronto Public Library. This exhibition highlighted everyday people who lived and worked in the city throughout the 20th century. The visages, drawn largely from the Toronto Star newspaper archives, told a unique tale of each person. Smolij became a celebrity in his day simply by enduring, i.e., sleeping only four hours and playing chess all night outside in all seasons.

Chess matches continued on at Yonge and Gould, which was named Hacksel Place in honor of another chess enthusiast, until 2003. Today, the street corner across from the Sam the Record Man store, which was the Mecca of chess in Toronto has withered away over time. The city allowed maintenance to slide and some of the seats at the chess tables are missing and the wood trim around their tops is rotting. While chess is still active in Toronto, it is not as colorful as the 1970s.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed